by Kathy Tretter

There can be no doubt about it — Eugene Stephens was a genius!

A deep thinker, he was on a philosophical and spiritual quest to understand the universe and his place in it. Eugene read voraciously, analyzed extensively and developed a profound world view that rivals the likes of Aristotle, Socrates and Nietzsche.

Oh, and did I mention he was a factory worker at Whirlpool living with his wife and two sons in Hatfield?

That he was. He rose every day and left the house at 5:30 a.m. but was home by 3:30 p.m. He didn’t plunk himself in front of a television when his workday was done. Instead he read or sculpted or painted or hand-tooled leather book covers or penned his deepest thoughts. Possibly more importantly he mulled the mysteries of existence and worked to understand things that most mortals never even consider.

Eugene Stephens was not only a genius, he was the epitome of a true renaissance man.

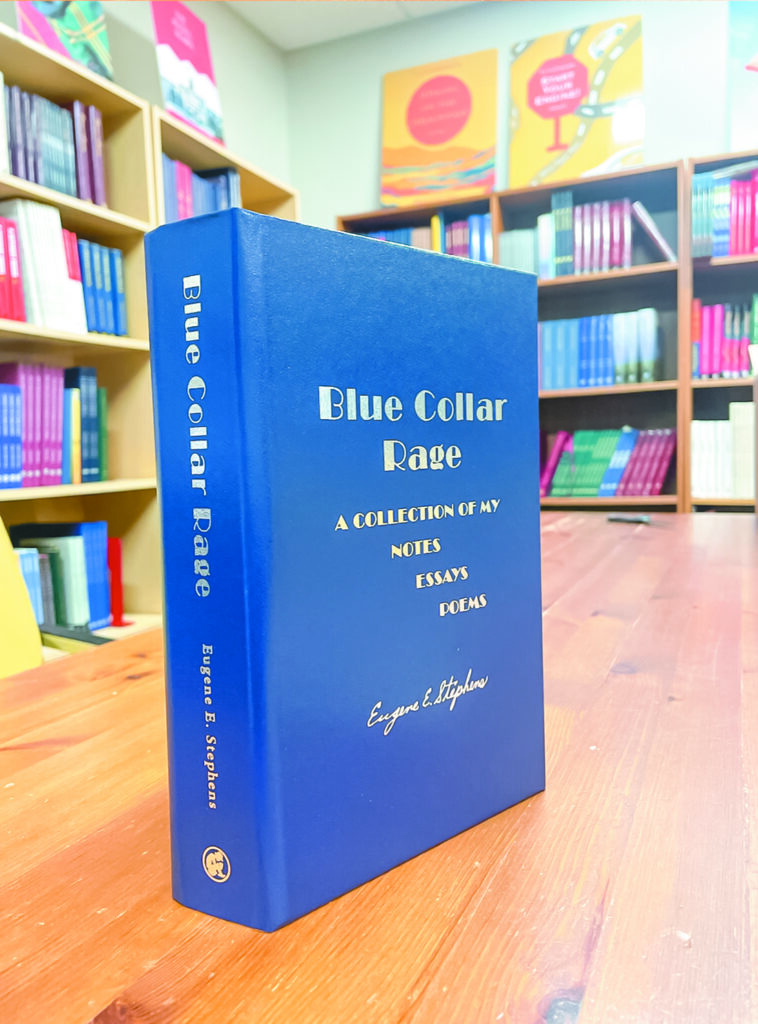

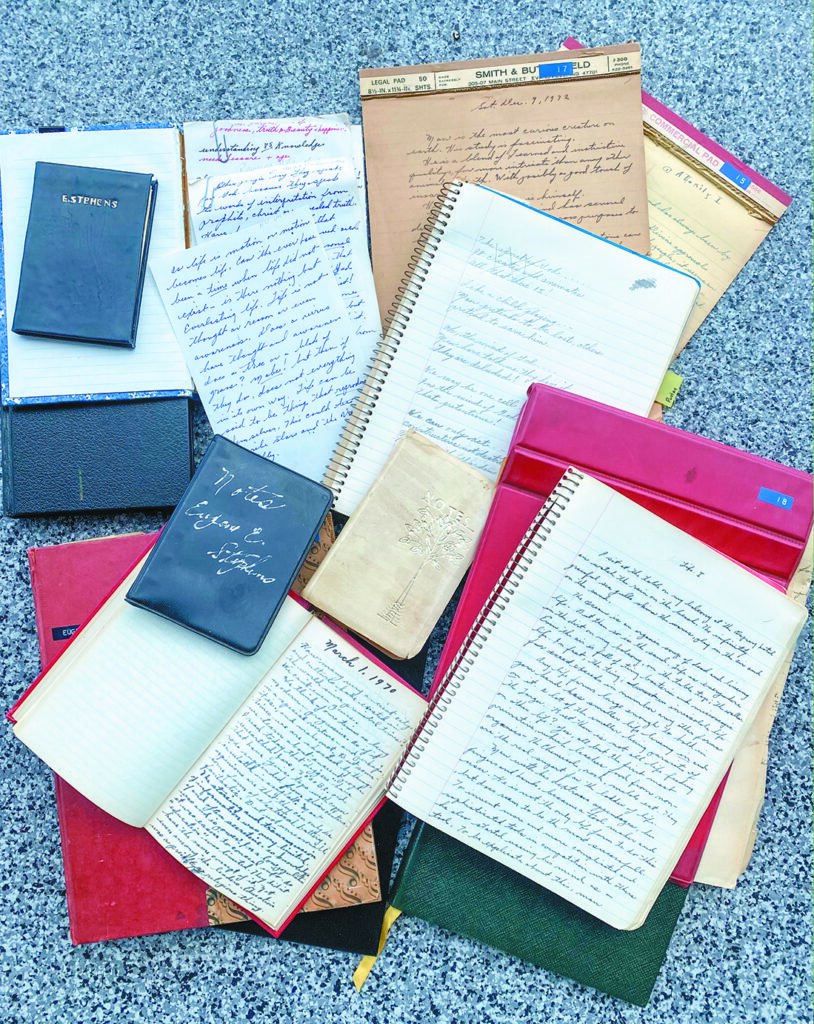

Throughout his lifelong journey of enlightenment, Stephens filled a massive number of journals with notes, essays and poems, cataloging his thoughts and impressions. He intended to one day turn his hand-written work into a book but this was not to be.

Eugene passed away on December 1, 1993, having spent just 68 years on this earth. But those 68 years were filled with countless hours spent reading and processing — learning just for the sake of expanding his knowledge and coming to terms with what it means to be human.

Upon Eugene’s death his son Andy inherited 32 notebooks filled with his father’s handwritten observances. All were dated so Andy could follow chronologically.

Andy spent five years typing his father’s musings exactly as written and then had copies made at Kinkos so he could pass on his dad’s vast wisdom to his and brother Alan’s children, grandchildren and future generations.

Last year Andy concluded his father’s ruminations should be available to a wider audience, so he had the book published in hardcover form, then he donated copies to the Spencer County Historical Society.

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

Eugene Stephens grew up on a farm near Chrisney. His parents did not own the farm. His dad, Ernie Stephens was a tenant farmer who hoed tobacco and raised crops for someone else in exchange for a roof over his and his family’s heads along with a little renumeration.

“When I asked my father why he never wore blue jeans,” Andy explains, “he said, “Son, I grew up every day wearing bibb overalls and blue jeans as a little boy helping my father work on the farm. I promised myself when I became an adult, I would never put on another pair of blue jeans.”

That doesn’t mean he wasn’t a hard worker. He absolutely was — and much like his father before, work served as an end to a means, it didn’t shape his identity. By working in a factory he was able to focus his attention after hours on things he held dear.

“In our house [in Hatfield] Dad had floor to ceiling bookcases along the whole wall,” Andy reports. “Reading was his way of soul searching. He was self-taught and self-inspired, always starved for intelligent conversation. You could randomly pick a topic and his in-depth knowledge was amazing.”

While not your typical kid, Eugene did follow the path of many of his brethren. Born in 1925 he was just the right age to serve in the military during WWII, opting to go Navy. Stationed on a destroyer in the Atlantic escorting convoys, he worked in the boiler room which probably allowed him time to ponder whatever it was he happened to be pondering as he handled his routine responsibilities.

“He valued his time in the Navy,” says Andy. “It allowed him to see the world and took him out of his environment.”

Before he enlisted Eugene just happened to meet a “city” girl, Helen Fisher. They started dating and continued to correspond.

One day Eugene received a letter from his sister, Maxine, who casually mentioned that Helen had a date [with someone else] the other night.

Apparently this was not good, at least in Eugene’s opinion. He managed to exchange leave with another sailor and hightailed it home so he could properly propose to the city girl he fell in love with.

By the way, the city where Helen lived was Rockport. She always made a point of saying Eugene was a country boy, and despite the fact he had toured the world and set foot in far flung places, a country boy he would always be.

After the war he enlisted in the Naval Reserve and was called up during the Korean Conflict. By this time Eugene and Helen were married and she traveled with him to San Diego.

Andy says his dad didn’t see any action but he and Helen did manage to conceive their first child while there.

Initially when they returned to Indiana they lived in Chandler, but Eugene’s folks had settled in Hatfield so when Eugene and Helen decided it was time to buy a house they found a place just a two doors down from his parents.

From all accounts Alan and Andy had a blessed, carefree childhood, roaming the streets of Hatfield, playing ball, riding their Schwinn banana bikes over hill and dale and hanging with their grandparents when their parents were working.

Did Eugene inherit his love of learning from his grandparents?

Andy doesn’t think so.

He recalled his grandpa asking him if he had any plans on Saturday. Andy did not, so he agreed to accompany Grandpa Ernie on an errand.

Turns out the two hoofed it to downtown Hatfield where, his grandpa informed him, “We’re going to dig a grave — by hand” — and they did.

It was as perfect as a grave dug by mechanical means would have been. But Ernie was more the physical type not given to deep thinking, whereas, “My Dad wasn’t a typical dad,” Andy explains. “He didn’t play sports with us kids, he was into his own hobbies and crafts.”

In the evening while the brothers and their mom watched TV their dad would be engrossed in a book, or out in his hobby room, essentially a utility room where the workings of the house were stored along with a workbench, where Eugene would paint and draw, or sculpt. He would also write in his journals.

As to his hobbies, once the learning curve flattened out he would lose interest to a degree and move on to something else.

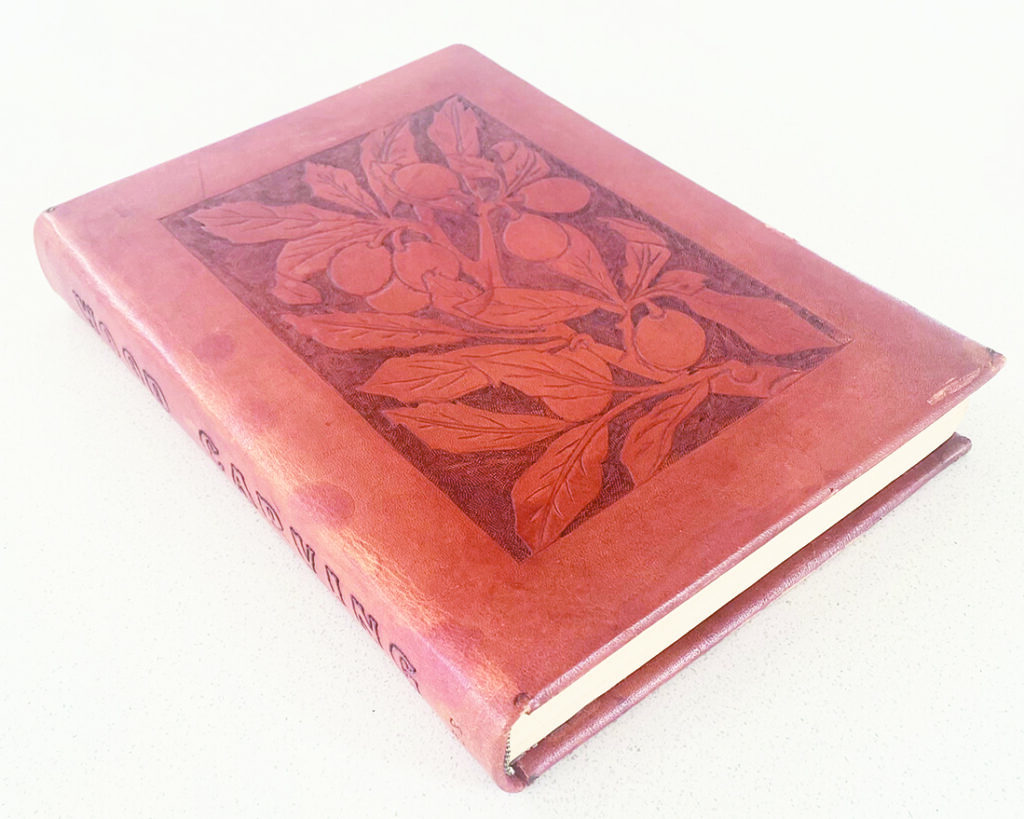

One of those “something elses” was book binding. He ordered a book to learn how to tool leather, starting with a billfold kit and moving on to the most elaborate patterns imaginable.

He would buy various grades of leather, then draw and design intricate patterns before working them into the hide.

“He then learned how to inset gold leaf and got incredibly proficient at it,” Andy remembers, after which he began crafting boxes to hold the books.

The following story illustrates the kind of man Eugene Stephens was.

Andy was home from Purdue for a visit and his dad showed him a beautiful book he had rebound, along with a case to contain it that he had crafted for a writer named Louis Ginsberg from Virginia. The two had been corresponding for some time and Louis often sent Eugene valuable books to repair or rebind.

“I thought it was pretty amazing and asked him how much he would make on it. My dad’s face fell, he looked so disappointed and said ‘Son, I don’t do this for the money. I do it for the love of the craft.’”

That essentially sums up the essence of Eugene Stephens. He didn’t rebind the book and create a box to nestle it in for the money, he did it for the love of this new skill and most certainly for the love of books.

While many of his passions had a decidedly renaissance feel, Eugene was no slouch in the technology department either.

In 1980 Andy bought his mother a Compaq Computer and had it shipped to his parents. His dad opened the package and started playing around with it — to the point he then taught himself how to code.

When Andy started his first company he bought a Tandy computer from Radio Shack but ran into a coding issue.

He called his dad for advice.

His dad teased him, saying, “Hey Mr. Big Shot Purdue engineer” — before telling him how to fix the problem.

“It was hard to get my dad out of the house. He was in his own cerebral world,” Andy says. Every so often his family would convince him to drive back to Evansville to dine out at Ponderosa, but that was about as far as he would go.

But later in life, after both sons were grown, a friend of Andy’s invited him and his dad on a father-son fishing trip to Canada with other fathers and sons. At first Eugene demurred but a plea from Andy to his mom and his mom to his dad made Eugene change his mind and agree to go.

The trip was magical in Andy’s memory. They fished and Andy saw a competitive side to his dad he’d never seen before. They saw the Northern Lights and enjoyed a special camaraderie with the other fathers and sons.

A similar trip was planned for Spring of 1993 and this time Andy called his brother, Alan, who was living and working in Hong Kong and asked if he could join them. Alan did and the trio again had a wonderful time sitting in a boat fishing for hours and then fascinating conversations.

It was the last time Alan would see his father alive. Eugene passed away a few short months later.

As stated earlier, Andy initially made copies of his dad’s journals for his family but later decided the collection was too valuable not to share with a broader audience.

His dad had even come up with the title, “Blue Collar Rage”.

This is not the type of book one sits down and consumes in one evening. It is philosophical, spiritual, knowledgeable. Reading it you can almost see the evolution of this man as he struggled to understand the meaning of life.

It is definitely worth reading and can be checked out from the Spencer County Public Library in Rockport as well as the Parker Branch Library in Hatfield, the Richland Library, as well as Lincoln Heritage Public Libraries in Dale and Chrisney.

Eugene Stephens was definitely a special man. His sons Andy says, “I always knew Dad was a pretty bright, smart guy. I didn’t understand why he didn’t [take advantage of] the GI Bill. But he was not ambitious in the traditional sense. Working in the welding department at Whirlpool gave him the space to do the things he wanted to do.”

As he transcribed his father’s journals Andy says he started to understand his father more fully and realized the sacrifices he made. “I started to appreciate Dad’s choices in life and to see his life and choices in a different perspective. This was a special gift.”

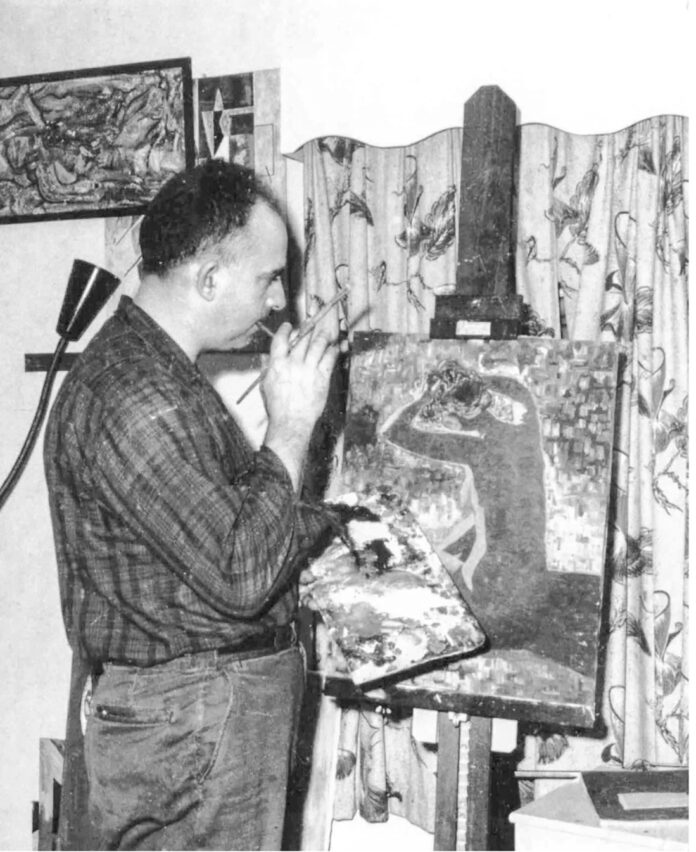

Featured Image: Eugene Stephens working on a painting.

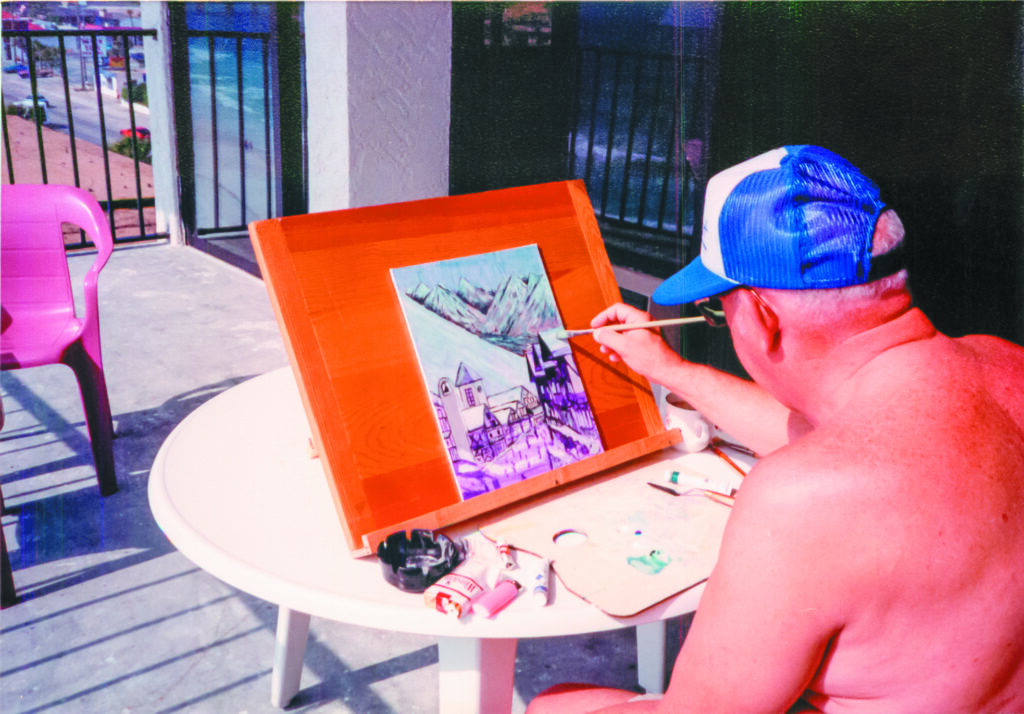

Pictured from upper left are: The book of Eugene Stephen’s writings published by his son, Andy Stephens; Eugene Stephens enjoying one of his hobbies; Another hobby was creating elegant etched leather book covers – a skill and art he taught himself; and Eugene’s journals. Andy compiled his father’s handwritten works to create the book which is available at the libraries in Rockport, Hatfield, Richland, Chrisney and Dale.