by Kathy Tretter

Possibly the biggest shock of Duane Walter’s military career did not come during Basic Training when he had to navigate through a series of gas jets — burning horizontally — on a hillside at Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio, Texas.

Nor did it come when he was put in a closed room filled with tear gas — with no gas mask.

It didn’t happen from the shock of cold when stationed in Alaska either.

Nope, Duane’s greatest shock came during the inauguration of the nation’s 35th president, John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Duane’s commander chose him to serve on the honor guard for the ceremony and Kennedy, along with Eisenhower, Johnson, Rust and possibly Nixon all bundled up and climbed into a convertible just a stones throw from where Duane was standing.

“Is this true?” Walter thought to himself on that historic day. “Could it be?”

Apparently it was — to a man, they were all wearing makeup — rouge, lipstick, possibly a little something to showcase their eyes. “I guess it was good color for the cameras,” Duane says today, although the first color television was not installed in a home until 1954, and six years later these marvels were still few and far between.

All sorts of memories from his time in service flooded back to Duane Walter during his recent (April 30) Honor Flight to Washington, DC. He had been scheduled to make the trip a couple years ago but that nasty pandemic got in the way, so this was the first Honor Flight since 2019. Duane’s daughter, Marla Scott, served as his companion.

For those who don’t know him, Duane Walter was a “Richland Red Devil,” graduating from high school in 1955. He enlisted in the Air Force in October of 1959 and did indeed have to wend his way through horizontal gas jets, suffer in a room with tear gas, as well as crawl through a minefield and sail across water on a rope swing. For that, the guy in front was supposed to push the rope back but if he didn’t the next guy had to take a leap of faith and hope he could reach the rope.

After basic he was sent to Amarillo, Texas for tech school, to be trained as an aircraft and airframe mechanic, specifically on B-47 bombers — the first jet powered bombers — and on the B-52. Walter specialized in inspecting the planes pre- and post-flight. His first assignment, which put him two months prior to JFK’s inauguration, was at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland where the team was responsible for a squadron of around one hundred planes (and from which he received the Honor Guard assignment).

One of his team must have had a touch of narcolepsy because he was always falling asleep in awkward situations, so much so that Duane’s radar was attuned to this guy’s foibles.

One time he found him sleeping in the cockpit — with his hand wrapped around the eject button. Duane was careful to awaken him in such a way he wouldn’t pull the lever, or else it would have shot him from the plane and likely would have killed him.

As part of the inspection the mechanics would have to crawl in the tailpipe to check for cracks and he found the same guy — asleep in the tailpipe.

“I learned to watch for him,” Duane explains. On that occasion he told him to “get out of there.”

Because his work was sensitive Duane does not have photos from his years in service. He spent two and a half years at Andrews and remembers when he needed to vote absentee he waited to find a high ranking officer to sign off on the ballot. “I waited until I had a general,” he says, figuring it would impress the folks back home.

At the time he was there, Duane remembers Andrews was home to both the Enola Gay (a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber that became the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in warfare on August 6, 1945, over Hiroshima) and an old F-80 — the first jet fighter used operationally.

If you had not already guessed the answer is yes, Duane Walter loves planes.

His next assignment took him to Galena, Alaska, across from Fairbanks on the Yukon River, where a military airfield was built adjacent to the city during World War II. The temperature sometimes hovered around 40 below and the village was peopled with Asiatic Indians whose diet consisted primarily of fish. “Those were some of the best fish I’ve ever seen,” Duane remembers, especially the king salmon.

There his squad specialized in scrambling — the act of quickly mobilizing military aircraft. He could still recite the steps it took to get ready to fly — a lengthy list to be sure — but the crew could and often did make it through in two minutes. From his post Duane says “You would see Russian planes once in a while,” which was likely why the base was situated in a frigid wasteland. He remembers that guards stood on every corner standing out in the cold with their rifles at the ready. The guards couldn’t see the mechanics and all wore mukluks to keep their feet warm.

Occasionally the airmen had a little time off to go exploring and would take out small boats or roam into old gold mining towns like Ruby, Alaska, where the tables in abandoned cabins were still set for dinner.

Sometimes the army would pay a visit and the commander would let the soldiers sleep on the floor in the unheated hangar. They would be dressed all in white to blend in with their surroundings.

Duane and his brethren had it a little better, occupying one room apartments in a dorm-like setting, three guys to a room. “They had everything real nice,” says Duane.

They could watch the one and only television station, but according to Duane all the food was brought once a year, so they never had milk or fresh anything. And sadly, “We ran out of my preferred beer.”

In the summer the mosquitoes were so bad they would dive bomb anybody not covered up and he remembers one officer who didn’t take the threat seriously and was so bitten up he had to be taken to the hospital.

While Duane’s beer was gone, he did find other pleasures. “Alaska was open gambling, night and day. We also had a pool table.”

Duane happened to still be in Alaska for the Cuban Missile Crisis. He said they got 20 planes ready and waiting on the tarmac “but then we didn’t send them off, we didn’t have to,” when the crisis was averted. The airmen didn’t really know what was going on so Duane checked with his dad back home for a report. “We had nuclear weapons there,” he adds, yet another reason he doesn’t have photos.

After four years of service Duane decided it was time to go home, but when he was discharged he went to California where his mom was living. He was fresh from the service and watching TV on Friday, November 22, 1963, at his mom’s when the news flashed on the screen: President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, at 12:30 p.m. CST in Dallas, Texas, while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza.

Basically, Duane Walter’s military service paralleled with that of the 35th president’s time in office.

Other than serving in the honor guard in 1960, the only trip Duane Walter made to Washington, DC was his senior class trip in 1955 — and much had changed in the intervening 66 years.

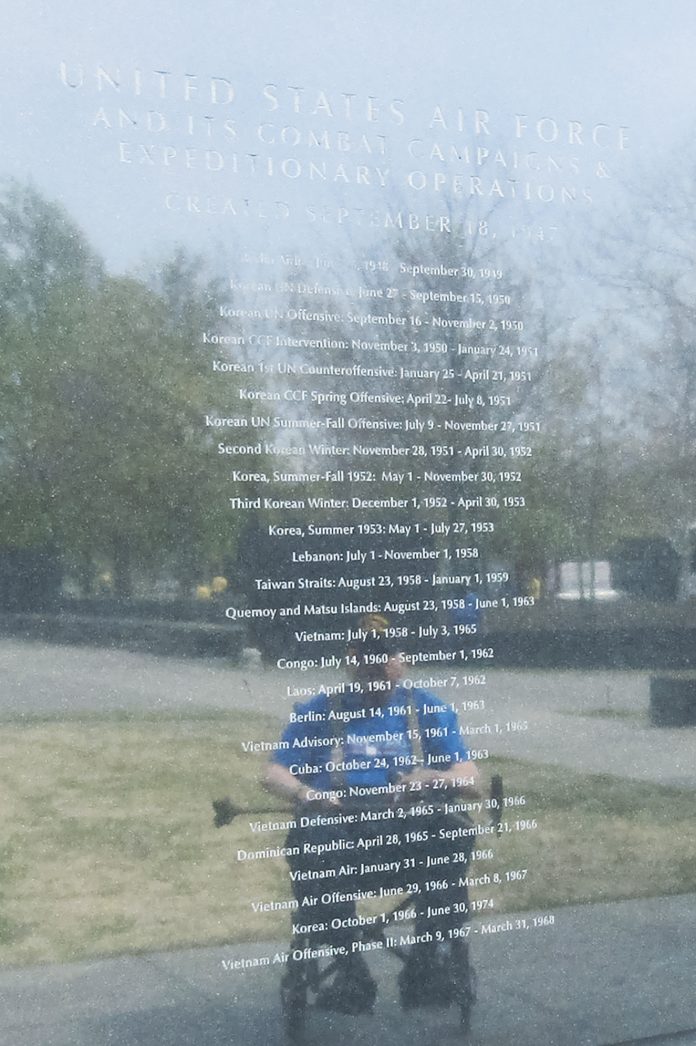

He had a wonderful time during the Honor Flight and was especially enamored with the Air Force memorial. He noticed, while at that memorial overlooking the Pentagon, the difference in the limestone color, “It doesn’t match,” where the Pentagon was struck on 9-11. He was fascinated with the changing of the guard and all the other sites, and was deeply touched by the letters.

Duane said during the day they honored the four veterans who were signed up for the trip and then passed away before they could go and he gives this advice to all veterans who have not taken advantage of the Honor Flight.

“You should go. They take good care of you.”

It was an adventure he will never forget.